This is a special edition article from The Sourdough People for those who seek maximum context while learning, as we strive to cater to diverse interest groups and readership styles. By offering in-depth explorations alongside more accessible content, we aim to provide a balanced approach across our published content.

In the realm of artisanal baking and microbial fermentation, the terms sourdough starter and sourdough culture are frequently conflated, yet they denote distinct entities with unique roles in the leavening process. To the uninitiated, they may appear synonymous, but to the seasoned baker or fermentation scientist, they represent two interdependent but separate systems of microbial life. A comprehensive understanding of their nuanced relationship necessitates an exploration into the microbiological and biochemical dynamics that govern spontaneous fermentation.

Defining the Fundamentals: Sourdough Starter and Sourdough Culture

Sourdough Culture: The Mother Matrix

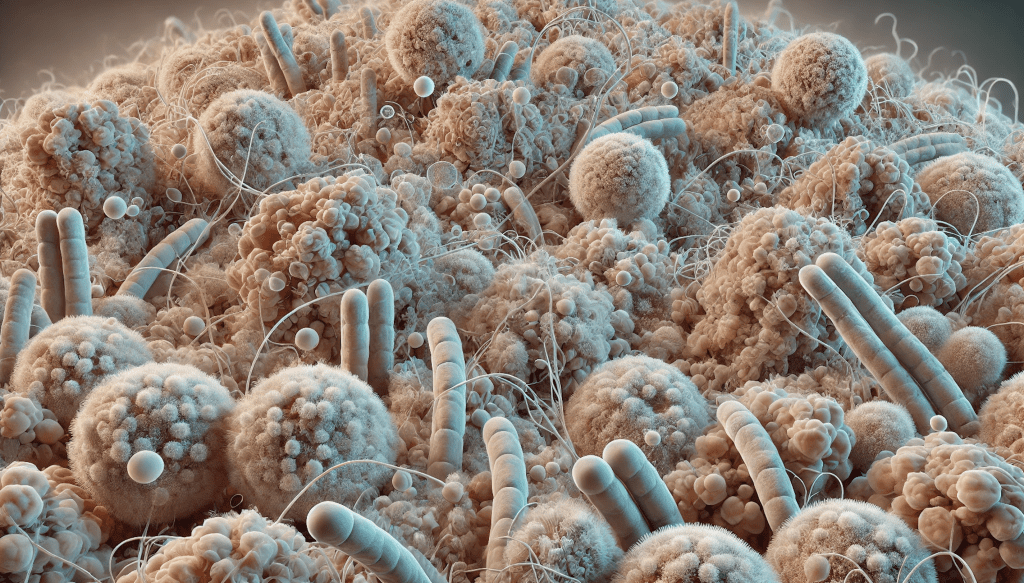

At the core of every authentic sourdough lies the sourdough culture—often revered as the mother. This culture is a complex, self-sustaining microbial ecosystem, predominantly composed of wild yeasts (mainly Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida milleri) and lactic acid bacteria (primarily Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Lactobacillus brevis). It embodies a living biome that undergoes continuous metabolic flux, maintaining a delicate equilibrium between microbial consortia, pH homeostasis, and nutrient cycling.

The sourdough culture is essentially a reservoir of microbial biodiversity and enzymatic potential. It serves as the primary inoculum that can be propagated indefinitely under controlled environmental parameters. Its resilience lies in its ability to enter a state of dormancy, preserving cellular integrity and genetic viability. This characteristic makes it ideal for long-term storage, whether in a refrigerated state to arrest metabolic processes or desiccated for preservation. Upon rehydration, the culture resumes its metabolic activity, maintaining continuity and consistency of the microbial community.

Sourdough Starter: The Active Agent

The sourdough starter is a derivative subset of the sourdough culture. It represents an activated inoculum—a subculture that is selectively propagated from the mother culture, optimized for vigorous fermentation kinetics and leavening efficacy. In scientific parlance, the starter is a transient, metabolically active population designed to maximize gas production and flavor development.

Unlike the mother culture, the starter undergoes systematic refreshment cycles, where flour and water are periodically introduced to stimulate exponential microbial proliferation. This controlled feeding regimen enhances enzymatic hydrolysis, generating fermentable sugars that fuel yeast respiration and lactic acid bacteria metabolism. Consequently, the starter reaches peak microbial density, producing substantial quantities of carbon dioxide and organic acids, crucial for dough leavening and flavor complexity.

The starter, therefore, acts as the kinetic catalyst in the fermentation continuum, driving the biochemical transformations that contribute to the organoleptic properties of sourdough bread. It is the dynamic engine of microbial metabolism, whereas the culture is the genetic repository and microbial reservoir.

Microbial Dynamics and Biochemical Interplay

Symbiotic Ecosystem

Both the sourdough culture and starter harbor a symbiotic microbial consortium where wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria engage in mutualistic interactions. The yeasts primarily ferment carbohydrates into ethanol and carbon dioxide, contributing to dough aeration and volume expansion. Concurrently, the lactic acid bacteria metabolize sugars through heterofermentative and homofermentative pathways, yielding lactic acid, acetic acid, and a spectrum of volatile compounds.

This biochemical synergy not only imparts the characteristic sour profile of traditional sourdough but also establishes an acidic environment that inhibits spoilage of microorganisms and pathogens. The low pH, coupled with the production of antifungal compounds like fatty acids and cyclic peptides, ensures the microbial stability and shelf-life of the final product.

Metabolic Differentiation

A critical distinction between the culture and the starter lies in their metabolic states and ecological niches. The sourdough culture is typically maintained in a quiescent state, characterized by low metabolic activity and slow substrate turnover. This dormant condition preserves microbial diversity and cellular viability over extended durations. Conversely, the starter exists in an active, exponential growth phase, optimized for rapid carbohydrate metabolism, gas production, and acidification.

This divergence in metabolic activity is orchestrated through specific environmental controls, including feeding frequency, hydration levels, and ambient temperature. These variables influence microbial growth kinetics, substrate utilization, and metabolic fluxes, ultimately dictating the leavening power, flavor complexity, and textural attributes of the sourdough.

Interconnectedness and Functional Relationship

From Culture to Starter: A Biotechnological Perspective

The relationship between the culture and the starter is analogous to that of a master seed and its propagative offspring. The culture serves as a genetic and microbial reservoir, ensuring the continuity and stability of the microbial ecosystem. When a portion is extracted and refreshed, it becomes a starter—an activated subset with enhanced metabolic activity tailored for immediate fermentation demands.

This biotechnological approach facilitates precise manipulation of fermentation dynamics. By selectively propagating the starter from the mother culture, one can modulate microbial population ratios, influencing the metabolic pathways that dictate flavor development, acid production, and dough rheology. This degree of microbial control underscores the necessity of distinguishing between the culture and the starter, as each serves a specialized role in the leavening process.

Reverting to the Culture: The Cyclical Continuum

After fulfilling its role in fermentation and leavening, the starter can be reintegrated into the mother culture. This cyclical continuum maintains the microbial equilibrium and genetic integrity of the culture while preserving the nuanced flavor compounds synthesized during fermentation. In this cyclical paradigm, the culture is the origin and repository of microbial diversity, whereas the starter is the ephemeral agent of activation and transformation.

Why the Distinction Matters: Practical and Theoretical Implications

Preservation and Longevity

Recognizing the distinction between sourdough culture and starter is fundamental for long-term preservation. The culture, maintained in a dormant state, safeguards microbial viability, enzymatic functionality, and genetic continuity. Conversely, the starter, due to its heightened metabolic activity, necessitates regular feeding and environmental control, rendering it unsuitable for prolonged storage without risking microbial imbalance or autolysis.

Flavor Profiling and Fermentation Control

Differentiating the culture from the starter grants precision over fermentation parameters. By selectively propagating the starter, bakers can modulate metabolic pathways, fine-tuning the production of organic acids, esters, and alcohols, which contribute to the sourdough’s complex flavor profile. This strategic control also influences dough rheology, crumb structure, and crust formation, enabling a tailored baking outcome.

Embracing the Complexity of Sourdough Fermentation

The distinction between sourdough starter and sourdough culture transcends mere nomenclature, embodying a sophisticated biotechnological system of microbial propagation and preservation. The culture is the genesis—a long-term reservoir of microbial diversity, enzymatic potential, and genetic continuity. The starter is its transient offspring—an activated fermentative agent optimized for leavening, flavor complexity, and dough development.

Together, they form an interconnected cycle of life, dormancy, and metabolic activity. By embracing this complexity, bakers and fermentation scientists can master the art and science of sourdough, exploring new dimensions of flavor, texture, and functionality. This nuanced understanding not only preserves the legacy of traditional sourdough baking but also propels it into new frontiers of culinary and scientific exploration.